An introduction to C++'s variadic templates: a thread-safe multi-type map

Posted on Mon 01 February 2016 in C++

Trivia:

One of our favorite motto in our C++ team at work is: you shall use dependency injections instead of singletons! It actually comes with our unit-testing strategy. If the various components of your architecture are too tightly coupled, it becomes a tremendous effort to deeply test small critical chunks of your code. Singletons are that kind of beast that revives itself without your permission and comes from hell to haunt your lovely unit-tests. Our main project being multi-threaded (hence highly bug-prone) and vital for the company, "singleton" became a forbidden word. Yet, our team recently started going down the dark path. Thanks to C++11 and its variadic templates, I carefully crafted a thread-safe multi-type map container that simplified our configuration reloading system and saved us from the dark side of the coder force. If you always wondered what are variadic templates, how C++11's tuples can be implemented, I am going to present these concepts in this post using my container as a cobaye.

Note: for the sake of your sanity and the fact that errare humanum est, this article might not be 100% accurate!

Why would I use a thread-safe multi-type map?

Let me explain our odyssey: we are working on a highly modular and multi-threaded application. One of its core feature is the ability to reload various configuration files or assets used by some components spread accross many threads and a giant hierarchy of objects. The reloading process is automic using Linux's inotify monitoring filesystem events. One thread is dedicated to the reception of filesystem events and must react accordingly by parsing any changes and pushing them to other threads. At first, we used, to pass-by any newly parsed asset, some thread-safe queues or something analog to go channels. Since we did not want to use singletons, we had to pass references to our queues all along our object hierarchy. Sadly, our queue implementation is one to one and supports only one type, none of our config/asset types share the same base-type. For each asset type and each component using this asset, we had to create a new queue and pass-it all along our hierarchy. That is certainely not convenient! What we really wanted was a hybrid class between a std::map and a std::tuple.

We could have used a std::map with Boost.Variant to store our items, using a type like the following "std::map< std::string, std::shared_ptr< Boost.Variant < ConfigType1, ConfigType2>>>". Boost.Variant permits to encapsulate a heterogeneous set of types without common base-type or base-class, which solves one of our point. Another solution would be to encapsulate manually all our configuration classes in the same familly of classes, that is pretty cumbersome. But anyway, std::map does not guaranty any safety if you are writing and reading at the same time on a map slot. Secondly, std::shared_ptr does guaranty a thread-safe destruction of the pointee object (i.e: the reference counter is thread-safe) but nothing for the std::shared_ptr object itself. It means that copying a std::shared_ptr that could potentially be modified from another thread, might lead to an undefined behaviour. Even if we were to encapsulate all these unsafe accesses with mutexes, we are still lacking a nice mechanism to get update notifications for our objects. We do not want to constantly poll the latest version and propagate it through our code. And finally, if that solution were elegant enough, why would I currently write this blog post?

C++11 brings another collection type called std::tuple. It permits to store a set of elements of heterogeneous types. Take a look at this short example:

auto myTuple = std::make_tuple("Foo", 1337, 42);

std::cout << std::get<0>(myTuple) << std::endl; // Access element by index: "Foo"

std::cout << std::get<1>(myTuple) << std::endl; // Access element by index: 1337

std::cout << std::get<2>(myTuple) << std::endl; // Access element by index: 42

std::cout << std::get<const char*>(myTuple) << std::endl; // Access element by type: "Foo"

// compilation error: static_assert failed "tuple_element index out of range"

std::cout << std::get<3>(myTuple) << std::endl;

// compilation error: static_assert failed "type can only occur once in type list"

std::cout << std::get<int>(myTuple) << std::endl;

Tuples are that kind of C++11 jewelry that should decide your old-fashioned boss to upgrade your team's compiler (and his ugly tie). Not only I could store a const char* and two ints without any compiling error, but I could also access them using compile-time mechanisms. In some way, you can see tuples as a compile-time map using indexes or types as keys to reach its elements. You cannot use an index out of bands, it will be catched at compile-time anyway! Sadly, using a type as a key to retrieve an element is only possible if the type is unique in the tuple. At my work, we do have few config objects sharing the same class. Anyway, tuples weren't fitting our needs regarding thread safety and update events. Let's see what we could create using tasty tuples as an inspiration.

Note that some tuples implementations were already available before C++11, notably in boost. C++11 variadic templates are just very handy, as you will see, to construct such a class.

A teaser for my repository class:

To keep your attention for the rest of this post, here is my thread-safe multi-type map in action:

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

#include <string>

#include "repository.hpp"

// Incomplete types used as compile-time keys.

struct Key1;

struct Key2;

// Create a type for our repository.

using MyRepository = Repository

<

Slot<std::string>, // One slot for std::string.

Slot<int, Key1>, // Two slots for int.

Slot<int, Key2> // Must be differentiate using "type keys" (Key1, Key2).

>;

int main()

{

MyRepository myRepository;

myRepository.emplace<std::string>("test"); // Construct the shared_ptr within the repository.

myRepository.emplace<int, Key1>(1337);

myRepository.set<int, Key2>(std::make_shared<int>(42)); // Set the shared_ptr manually.

// Note: I use '*' as get returns a shared_ptr.

std::cout << *myRepository.get<std::string>() << std::endl; // Print "test".

std::cout << *myRepository.get<int, Key1>() << std::endl; // Print 1337.

std::cout << *myRepository.get<int, Key2>() << std::endl; // Print 42.

std::cout << *myRepository.get<int>() << std::endl;

// ^^^ Compilation error: which int shall be selected? Key1 or Key2?

auto watcher = myRepository.getWatcher<std::string>(); // Create a watcher object to observe changes on std::string.

std::cout << watcher->hasBeenChanged() << std::endl; // 0: no changes since the watcher creation.

myRepository.emplace<std::string>("yo"); // Emplace a new value into the std::string slot.

std::cout << watcher->hasBeenChanged() << std::endl; // 1: the std::string slot has been changed.

std::cout << *watcher->get() << std::endl; // Poll the value and print "yo".

std::cout << watcher->hasBeenChanged() << std::endl; // 0: no changes since the last polling.

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

First and foremost, its name repository might not be well-suited for its responsibility. If your native language is the same as shakespeare and come-up with a better term, please feel free to submit it. In our internal usage, config repository sounded great!

I start by describing the slots necessary for my application by creating a new type MyRepository using a type alias. As you can see, I use the type of the slots as a key for accessing elements. But in case of contention, I must use a second key: an "empty type" ; like Key1 and Key2 in this example. If using types as keys seems odd for you, fear not! Here is the most rational explanation I can share with you: we are trying to benefit from our "know-it-all compiler". Your compiler is mainly manipulating types, one can change its flow using these types during the compilation process. Note that these structs are not even complete (no definition), it has no impact for the runtime memory or runtime execution and that's the amazing part of meta-programming. The dispatch of an expression such as "myRepository.get< int, Key1>()" is done during your build-time.

You may also notice that every slot is actually a std::shared_ptr. It enforces a clean ressource management: in a multithreaded application, one must be really careful of the lifetime of heap objects. std::shared_ptr in this case permits me to ensure that even if someone replaces a value in a slot, other components on other threads manipulating the old value won't end up with a dangling pointer/reference bomb in their hands. Another solution would be to use plain value objects, but not only it would require copying big objects in every other components but it would also remove polymorphism.

As for the updates signalisation, you first create a watcher object that establishes a contract between a desired slot to watch and your context. You can thereafter query in thread-safe way weither an update has been made and, if so, poll the latest changes. The watcher object is actually a std::unique_ptr for a special class, it cannot be moved nor copied without your permission and will automagically disable the signalisation contract between the slot and your context, once destroyed. We will dive deeper in this topic in the comming sections.

Within our application, the repository object is encapsulated into a RuntimeContext object. This RuntimeContext object is created explicitely within our main entry point and passed as a reference to a great part of our components. We therefore keep the possibility to test our code easily by setting this RuntimeContext with different implementations. Here is a simplified version of our usage:

// runtimecontext.hpp

#include "repository.hpp"

// Incomplete types used as compile-time keys.

struct Key1;

struct Key2;

class ConfigType1; // Defined in another file.

class ConfigType2; // Defined in another file.

// Create a type for our repository.

using ConfigRepository = Repository

<

Slot<ConfigType1>,

Slot<ConfigType2, Key1>,

Slot<ConfigType2, Key2>

>;

struct RuntimeContext

{

ILogger* logger;

// ...

ConfigRepository configRepository;

};

// Main.cpp

#include "runtimecontext.hpp"

int main()

{

RuntimeContext runtimeContext;

// Setup:

runtimeContext.logger = new StdOutLogger();

// ...

// Let's take a reference to the context and change the configuration repository when necessary.

startConfigurationMonitorThread(runtimeContext);

// Let's take a reference and pass it down to all our components in various threads.

startOurApplicationLogic(runtimeContext);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

Time for a C++11 implementation:

We can decompose the solution in 3 steps: at first we need to implement a map that accepts multiple types, we then need to work on the thread safety and finish by the watcher mechanism. Let's first fulfill the mission of this post: introducing you to variadic templates to solve the multiple-type problem.

Variadic templates:

You may not have heard of variadic templates in C++11 but I bet that you already used variadic functions like printf in C (maybe in a previous unsafe life). As wikipedia kindly explains "a variadic function is a function of indefinite which accepts a variable number of arguments". In other words, a variadic function has potentially an infinite number of parameters. Likewise, a variadic template has potentially an infinite number of parameters. Let's see how to use them!

Usage for variadic function templates:

Let's say that you wish to create a template that accept an infinite number of class as arguments. You will use the following notation:

template <class... T>

You specify a group of template parameters using the ellipsis notation named T. Note that this ellipsis notation is consistent with C's variadic function notation. This group of parameters, called a parameter-pack, can then be used in your function template or your class template by expanding them. One must use the ellipsis notation again (this time after T) to expand the parameter pack T:

template <class... T> void f(T...)

// ^ pack T ^expansion

{

// Your function content.

}

Now that we have expanded T, what can we do Sir? Well, first you give to your expanded parameter types, a fancy name like t.

template <class... T> void f(T... t)

// ^ your fancy t.

{

// Your function content.

}

If T = T1, T2, then T... t = T1 t1, T2 t2 and t = t1, t2. Brilliant, but is that all? Sure no! You can then expand again t using an "suffix-ellipsis" again:

template <class... T> void f(T... t)

{

anotherFunction(t...);

// ^ t is expanded here!

}

Finally, you can call this function f as you would with a normal function template:

template <class... T> void f(T... t)

{

anotherFunction(t...);

}

f(1, "foo", "bar"); // Note: the argument deduction avoids us to use f<int, const char*, const char*>

// f(1, "foo", "bar") calls a generated f(int t1, const char* t2, const char* t3)

// with T1 = int, T2 = const char* and T3 = const char*,

// that itself calls anotherFunction(t1, t2, t3) equivalent to call anotherFunction(1, "foo", "bar");

Actually, the expansion mechanism is creating comma-separated replication of the pattern you apply the ellipsis onto. If you think I am tripping out with template-related wording, here is a much more concret example:

template <class... T> void g(T... t)

{

anotherFunction(t...);

}

template <class... T> void f(T*... t)

{

g(static_cast<double>(*t)...);

}

int main()

{

int a = 2;

int b = 3;

f(&a, &b); // Call f(int* t1, int* t2).

// Do a subcall to g(static_cast<double>(*t1), static_cast<double>(*t2)).

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

I could use the pattern '*' for f parameters and therefore take them as a pointer! In the same manner, I applied the pattern 'static_cast< double>(*) to get the value of each arguments and cast them as doubles before forwarding them to g.

One last example before moving to variadic class templates. One can combine "normal" template parameters with parameter packs and initiate a compile recursion on function templates. Let's take a look at this printing function:

#include <iostream>

template <class HEAD> void print(HEAD head)

{

std::cout << "Stop: " << head << std::endl;

}

template <class HEAD, class... TAIL> void print(HEAD head, TAIL... tail)

{

std::cout << "Recurse: " << head << std::endl;

print(tail...);

}

int main()

{

print(42, 1337, "foo");

// Print:

// Recurse: 42

// Recurse: 1337

// Stop: foo

// Call print<int, int, const char*> (second version of print).

// The first int (head) is printed and we call print<int, const char*> (second version of print).

// The second int (head again) is printed and we call print<const char*> (first version of print).

// We reach recursion stopping condition, only one element left.

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

Variadic templates are very interesting and I wouldn't be able to cover all their features within this post. It roughly feels like functional programming using your compiler, and even some Haskellers might listen to you if you bring that topic during a dinner. For those interested, I would challenge them to write a type-safe version of printf using variadic templates with the help of this reference. After that, you will run and scream of fear at the precense of C's vargs.

"Variadic" inheritance:

Sometimes during my programming sessions, I have a very awkward sensation that my crazy code will never compile and, yet, I finally see "build finished" in my terminal. I am talking about that kind of Frankenstein constructions:

struct A { };

struct B { };

template <class... T>

struct C: public T... // Variadic inheritance

{

};

C<A, B> c;

Yes, we can now create a class inheriting of an infinite number of bases. If you remember my explanation about pattern replications separated by commas, you can imaginge that struct C: public T... will be "transformed" in struct C: public A, public B, public T being the pattern. We start to be able to combine multiple types, each exposing a small amount of methods, to create a flexible concret type. That's one step closer to our multi-type map, and if you are interested in this concept, take a look at mixins.

Instead of inheriting directly from multiple types, couldn't we inherit from some types that encapsulate our types? Absolutely! A traditional map has some slots accessible using keys and these slots contain a value. If you give me base-class you are looking for, I can give you access to the value it contains:

#include <iostream>

struct SlotA

{

int value;

};

struct SlotB

{

std::string value;

};

// Note: private inheritance, no one can access directly to the slots other than C itself.

struct Repository: private SlotA, private SlotB

{

void setSlotA(const int& value)

{

// I access the base-class's value

// Since we have multiple base with a value field, we need to "force" the access to SlotA.

SlotA::value = value;

}

int getSlotA()

{

return SlotA::value;

}

void setSlotB(const std::string& b)

{

SlotB::value = b;

}

std::string getSlotB()

{

return SlotB::value;

}

};

int main()

{

Repository r;

r.setSlotA(42);

std::cout << r.getSlotA() << std::endl; // Print: 42.

r.setSlotB(std::string("toto"));

std::cout << r.getSlotB() << std::endl; // Print: "toto".

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

This code is not generic at all! We know how to create a generic Slot using a simple template, and we acquired the magic "create varidiac inheritance" skill. If my Repository class inherit from Slot< TypeA> and you call a method template with TypeA as a template argument, I can call the doGet method of the Slot< TypeA> base-class and give you back the value of TypeA in that repository. Let's fix the previous ugly copy-paste code:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

template <class Type>

class Slot

{

protected:

Type& doGet() // A nice encapsulation, that will be usefull later on.

{

return value_;

}

void doSet(const Type& value) // Same encapsulation.

{

value_ = value;

}

private:

Type value_;

};

template <class... Slots>

class Repository : private Slots... // inherit from our slots...

{

public:

template <class Type> // Give me a type and,

Type& get()

{

return Slot<Type>::doGet(); // I can select the Base class.

}

template <class Type>

void set(const Type& value)

{

Slot<Type>::doSet(value);

}

};

// Incomplete types used as compile-time keys.

struct Key1;

struct Key2;

// Create a type for our repository.

using MyRepository = Repository

<

Slot<int>, // Let's pick the type of our slots.

Slot<std::string>

>;

int main()

{

MyRepository myRepository;

myRepository.set<std::string>("toto");

myRepository.set(42); // Notice the type deduction: we pass an int, so it writes in the int slot.

std::cout << myRepository.get<int>() << std::endl; // Print: "toto".

std::cout << myRepository.get<std::string>() << std::endl; // Print: 42.

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

This repository starts to take shape, but we are not yet done! If you try to have two int slots, you will raise a compilation error: "base class 'Slot

struct DefaultSlotKey; // No needs for a definition

template <class T, class Key = DefaultSlotKey> // The Key type will never be trully used.

class Slot

{

// ...

};

template <class... Slots>

class Repository : private Slots...

{

public:

template <class Type, class Key = DefaultSlotKey> // The default key must be here too.

Type& get()

{

return Slot<Type, Key>::doGet();

}

template <class Type, class Key = DefaultSlotKey>

void set(const Type& value)

{

Slot<Type, Key>::doSet(value);

}

};

struct Key1; // No need for definition.

struct Key2;

// Now you can do:

using MyRepository = Repository

<

Slot<int>, // Let's pick the type of our slots.

Slot<std::string, Key1>,

Slot<std::string, Key2>

>;

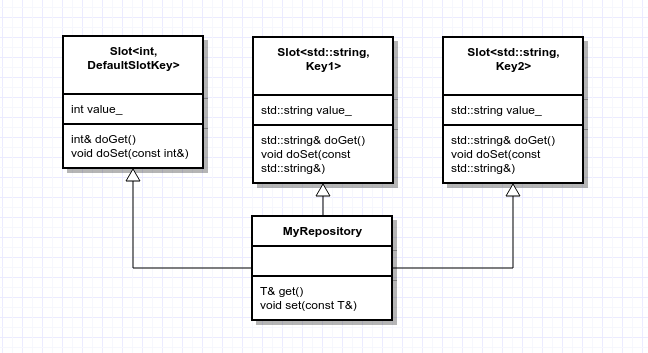

Here is a UML representation of this Repository using distinct Keys for the type std::string:

Our repository class is missing an emplace method, right? emplace is taking a variable number of arguments with different types and forward them to create an object within one of our slots. A variable number of arguments and types must remind you something... variadic templates! Let's create this variadic emplace method as well as its equivalent in the Slot class:

// In class Slot:

template <class... Args>

void doEmplace(const Args&... args) // Here the pattern is const &.

{

value_ = Type(args...); // copy-operator (might use move semantics).

}

// In class Repository:

template <class Type, class Key = DefaultSlotKey, class... Args>

void emplace(const Args&... args) // Here the pattern is const &.

{

Slot<Type, Key>::doEmplace(args...);

}

// Usage:

myRepository.emplace<std::string>(4, 'a'); // Create a std::string "aaaa".

One last improvement for the future users of your repositories! If one morning, badly awake, a coworker of yours is trying to get a type or key that doesn't exist (like myRepository.get< double>();), he might be welcomed by such a message:

/home/jguegant/Coding/ConfigsRepo/main.cpp:36:33: error: call to non-static member function without an object argument

return Slot<Type, Key>::doGet();

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~^~~~~

/home/jguegant/Coding/ConfigsRepo/main.cpp:67:18: note: in instantiation of function template specialization 'Repository<Slot<int, DefaultSlotKey>, Slot<std::__1::basic_string<char>, DefaultSlotKey> >::get<double, DefaultSlotKey>' requested here

myRepository.get<double>();

^

/home/jguegant/Coding/ConfigsRepo/main.cpp:36:33: error: 'doGet' is a protected member of 'Slot<double, DefaultSlotKey>'

return Slot<Type, Key>::doGet();

^

/home/jguegant/Coding/ConfigsRepo/main.cpp:10:11: note: declared protected here

Type& doGet()

^

2 errors generated.

This message is very confusing, our class does not inherit from Slot< double, DefaultSlotKey>! And we are talking about a clang output, I wonder what gcc or MSVC could produce... If you do not want to be assinated from your moody colleague with a spoon, here is a nice solution using C++11's static_asserts. Static asserts give you the possibility to generate your own compiler error messages in the same fashion as normal asserts but at compile-time. Using a the trait like std::is_base_of, you can suggest the user of your repository to check twice his type. Let's put this static_assert at the beggining of all the methods of Repository:

static_assert(std::is_base_of<Slot<Type, Key>, Repository<Slots...>>::value,

"Please ensure that this type or this key exists in this repository");

We are done for this part (finally...), time to think about multi-threading! If you want to know more about the magic behind std::is_base_of, I would suggest you to read my previous post on SFINAE, it might give you few hints. Here is a gist of what we achieved so far. Did you notice the change on emplace? If you do not understand it, have a look at this explanation on perfect forwarding. Sadly, it would be a way too long topic for this post (trust me on that point!) and has a minor impact on our repository right now.

Let's play safe:

The repository we just succeeded to craft can now be used in a single-thread environment without further investigation. But the initial decision was to make this class manipulable from multiple-threads without any worries considering the safety of our operations. As explained in the beginning of this post, we will not use direct values as we currently do, but instead allocate our objects on the heap and use some shared pointers to strictly control their lifetime. No matter which version (recent or deprecated) of the object a thread is manipulating, it's lifetime will be extended until the last thread using it definitely release it. It also implies that the objects themselves are thread-safe. In the case of read-only objects like configs or assets, it shouldn't be too much a burden. In this gist, you will find a repository version using std::shared_ptrs.

std::shared_ptr is an amazing feature of C++11 when dealing with multi-threading, but has its weakness. Within my code (in the previous gist link) a race condition can occur:

// What if I try to copy value_ at the return point...

std::shared_ptr<Type> doGet() const

{

return value_;

}

// ... meanwhile another thread is changing value_ to value?

void doSet(const std::shared_ptr<Type> &value)

{

value_ = value;

}

As specified: "If multiple threads of execution access the same std::shared_ptr object without synchronization and any of those accesses uses a non-const member function of shared_ptr then a data race will occur". Note that we are talking about the same shared pointer. Multiple shared pointer copies pointing to the same object are fine, as long as these copies originated from the same shared pointer in first place. Copies are sharing the same control block, where the reference counters (one for shared_ptr and one for weak_ptr) are located, and the specification says "the control block of a shared_ptr is thread-safe: different std::shared_ptr objects can be accessed using mutable operations, such as operator= or reset, simultaneously by multiple threads, even when these instances are copies, and share the same control block internally.".

Depending on the age of your compiler and its standard library, I suggest two solutions:

1) A global mutex:

A straightforward solution relies on a std::mutex that we lock during doGet and doSet execution:

...

std::shared_ptr<Type> doGet()

{

// The lock is enabled until value_ has been copied!

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mutex_);

return value_;

}

void doSet(const std::shared_ptr<Type> &value)

{

// The lock is enabled until value has been copied into value!

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mutex_);

value_ = value;

}

private:

std::mutex mutex_;

...

This solution is ideal if you have a Linux distribution that only ships gcc 4.8.x like mine. While not particularly elegant, it doesn't have a great impact on performances compared to the next solution.

2) Atomic access functions:

Starting from gcc 4.9, one can use atomic access functions to manipulate shared pointers. I dream of a day where a specialisation for std::atomic< std::shared_ptr

...

std::shared_ptr<Type> doGet() const

{

return std::atomic_load(&value_);

}

void doSet(const std::shared_ptr<Type> &value)

{

std::atomic_exchange(&value_, value);

}

private:

std::shared_ptr<Type> value_;

...

Atomics are elegants and can often bring a great increase of performances if using lock-free instructions internally. Sadly, in the case of shared_ptrs, atomic_is_lock_free will return you false. By digging in libstdc++ and libc++, you will find some mutexes. gcc seems to use a fixed size "pool" of mutexes attributed to a shared_ptr according to a hash of its pointee address, when dealing with atomic operations. In other words, no rocket-science for atomic shared pointers until now.

Our own watchers:

"...I shall live and die at my post. I am the sword in the darkness. I am the watcher on the walls. I am the shield that guards the realms of men..." -- The Night's Watch oath

We want to be able to seal a bond between one of the slot and a context. By context, I mean the lifetime of an object in a thread, a function or a method. If an update has been made on that slot, we must be signaled in that context and to retrieve the new update. The bond must be destroyed if the context does not exist anymore. It should reminds you the Night's Watch oath ... as well as the RAII idiom: "holding a resource is tied to object lifetime: resource acquisition is done during object creation, by the constructor, while resource deallocation is done during object destruction, by the destructor. If objects are destroyed properly, resource leaks do not occur.". A strong ownership policy can be obtained with the help of a std::unique_ptr and the signalisation can be done using a boolean flag.

We will, therefore, encapsulate a std::atomic_bool into a class Watcher automagically registered to a slot once created, and unregistered once destructed. This Watcher class also takes as a reference the slot in order to query its value as you can see:

template <class Type, class Key>

class Watcher

{

public:

Watcher(Slot<Type, Key>& slot):

slot_(slot),

hasBeenChanged_(false)

{

}

Watcher(const Watcher&) = delete; // Impossible to copy that class.

Watcher & operator=(const Watcher&) = delete; // Impossible to copy that class.

bool hasBeenChanged() const

{

return hasBeenChanged_;

}

void triggerChanges()

{

hasBeenChanged_ = true;

}

auto get() -> decltype(std::declval<Slot<Type, Key>>().doGet())

{

hasBeenChanged_ = false; // Note: even if there is an update of the value between this line and the getValue one,

// we will still have the latest version.

// Note 2: atomic_bool automatically use a barrier and the two operations can't be inversed.

return slot_.doGet();

}

private:

Slot<Type, Key>& slot_;

std::atomic_bool hasBeenChanged_;

};

As for the automatic registration, we will add two private methods registerWatcher and unregisterWatcher to our Slot class that add or remove a watcher from an internal list. The list is always protected, when accessed, with a std::mutex and tracks all the current watchers that must be signaled when set is called on that slot.

template <class Type, class Key>

class Slot

{

public:

using ThisType = Slot<Type, Key>;

using WatcherType = Watcher<Type, Key>;

...

private:

void registerWatcher(WatcherType* newWatcher)

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> l(watchers_mutex_);

watchers_.push_back(newWatcher);

}

void unregisterWatcher(WatcherType *toBeDelete)

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> l(watchers_mutex_);

watchers_.erase(std::remove(watchers_.begin(), watchers_.end(), toBeDelete), watchers_.end());

delete toBeDelete; // Now that we removed the watcher from the list, we can proceed to delete it.

}

void signal()

{

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> l(watchers_mutex_);

for (auto watcher : watchers_) {

watcher->triggerChanges(); // Let's raise the hasBeenChanged_ atomic boolean flag.

}

}

private:

std::vector<WatcherType*> watchers_; // All the registered watchers are in that list.

...

};

You may have notice that we are passing a bare WatcherType pointers. The ownership is actually given to whoever is using that watcher encapsulated within a std::unique_ptr. C++11's unique pointers are designed such as you can pass a custom deleter, or a delete callback so to speak. Hence, we can create a method that get a Watcher for a Slot, and register as the deleter of that Watcher a lambda function designed to call unregisterWatcher. Note that the slot MUST always lives longer than the unique pointer and its associated watcher (it should not be a problem in most cases). Let's finish that Slot class forever and ever:

template <class Type, class Key>

class Slot

{

public:

using ThisType = Slot<Type, Key>;

using WatcherType = Watcher<Type, Key>;

// We use unique_ptr for a strong ownership policy.

// We use std::function to declare the type of our deleter.

using WatcherTypePtr = std::unique_ptr<WatcherType, std::function<void(WatcherType*)>> ;

...

public:

WatcherTypePtr doGetWatcher()

{

// Create a unique_ptr and pass a lambda as a deleter.

// The lambda capture "this" and will call unregisterWatcher.

WatcherTypePtr watcher(new WatcherType(*this), [this](WatcherType* toBeDelete) {

this->unregisterWatcher(toBeDelete);});

registerWatcher(watcher.get());

return watcher;

}

...

};

Are we done? Hell no, but we will be really soon. All we need is to expose the possibility to acquire a watcher from the repository itself. In the same manner as set and get, we simply dispatch using the type and the key on one of our slot:

template <class Type, class Key = DefaultSlotKey>

typename Slot<Type, Key>::WatcherTypePtr getWatcher() // typename is used for disambiguate

{

return Slot<Type, Key>::doGetWatcher();

}

WAIT, don't close that page too fast. If you want to be able to snub everyone, you can replace this ugly typename Slot

Conclusion:

Once again, I hope you enjoyed this post about one of my favourite subject: C++. I might not be the best teacher nor the best author but I wish that you learnt something today! Please, if you any suggestions or questions, feel free to post anything in the commentaries. My broken English being what it is, I kindly accept any help for my written mistakes.

Many thanks to my colleagues that greatly helped me by reviewing my code and for the time together.