Meta Crush Saga: a C++17 compile-time game

Posted on Sat 19 May 2018 in C++

Trivia:

As a quest to obtain the highly coveted title of Lead Senior C++ Over-Engineer, I decided last year to rewrite the game I work on during daytime (Candy Crush Saga) using the quintessence of modern C++ (C++17). And... thus was born Meta Crush Saga: a compile-time game. I was highly inspired by Matt Bernier's Nibbler game that used pure template meta-programming to recreate our the famous snake game we could play on our Nokia 3310 back in the days.

"What the hell heck is a compile-time game?", "How does it looks like?", "What C++17 features did you use in this project?", "What was your learnings?" might come to your mind. To answer these questions you can either read the rest of this post or accept your inner laziness and watch the video version of this post, which is a talk I made during a Meetup event in Stockholm:

Disclaimer: for the sake of your sanity and the fact that errare humanum est, this article might contain some alternative facts.

A compile-time game you said?

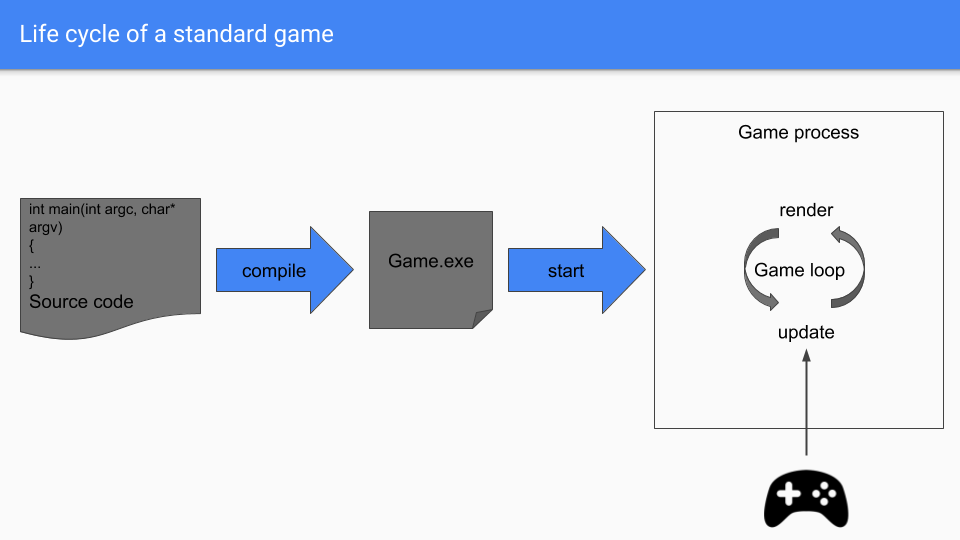

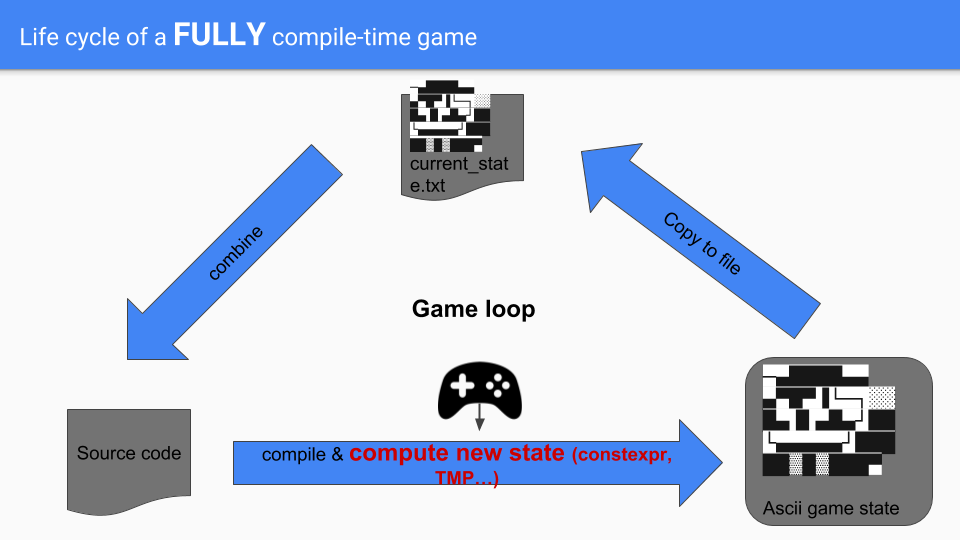

I believe that it's easier to understand what I mean by the "concept" of a compile-time game if you compare the life cycle of such a game with the life cycle of a normal game. So here it is!

Life cycle of a normal game:

As a normal game developer with a normal life working at a normal job with a normal sanity level you would usually start by writing your game logic using your favorite language (C++ of course!), then fire your compiler to transform this, far too often spaghetti-like, logic into an executable. As soon as you double-click on your executable (or use the console), a process will be spawned by your operating system. This process will execute your game logic which 99.42% of time consists of a game loop. A game loop will update the state of your game according to some rules and the user inputs, render the newly computed state of your game in some flashy pixels, again, again and again.

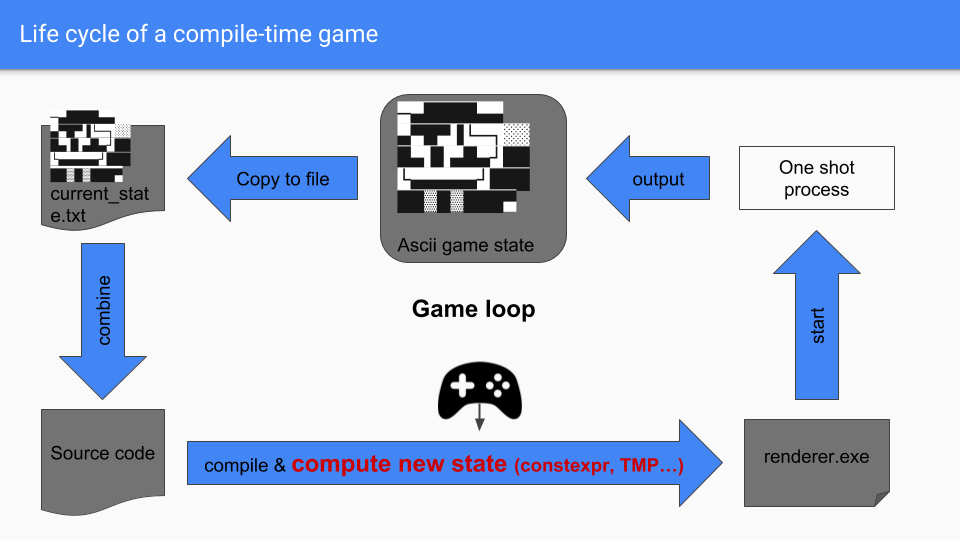

Life cycle of a compile-time game:

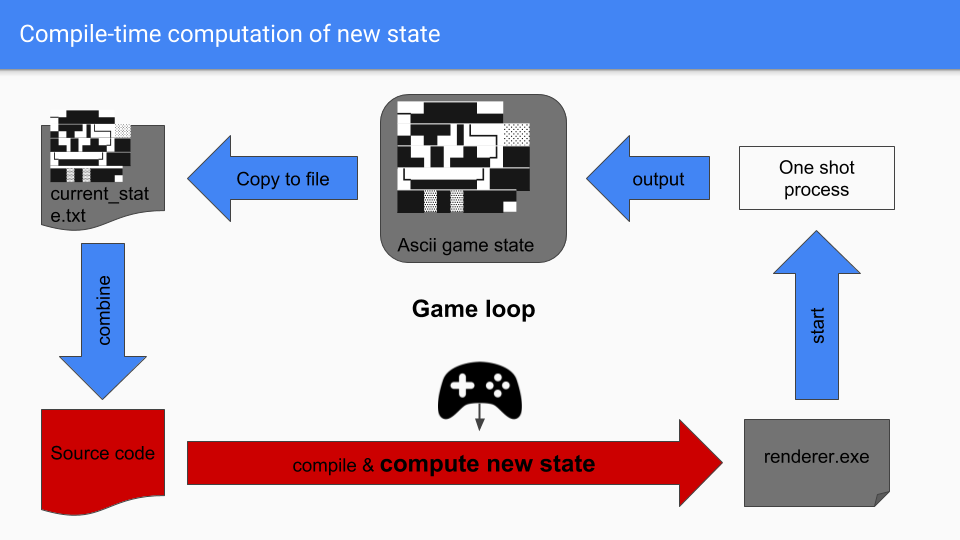

As an over-engineer cooking the next big compile-time game, you will still have use of your favorite language (still C++ of course!) to write your game logic. You will still have a compilation phase but... then... here comes the plot twist: you will execute your game logic within this compilation step. One could call it a compilutation. This is where C++ truly comes in handy ; it has a some features like Template Meta Programming (TMP) or constexpr to actually have computations happening during the compilation phase. We will dive later on the features you can use to do so. As we are executing the logic of the game during this phase, we must also inject the user inputs at that point in time. Obviously, our compiler will still output an executable. What could it be used for? Well, the executable will not contain any game loop anymore, but it will have a very simple mission: output the newly computed state. Let's name this executable a renderer and its output the rendering. Our rendering won't contain any fancy particule effect nor ambiant occlusion shadows, it will be in ASCII. An ASCII rendering of your newly computed state has the nice property that you can easily show it to your player, but you also copy it into a text file. Why a text file? Obviously because you can combine it with your code in some way, redo all the previous steps and therefore have a loop.

As you may understand now, a compile-time game is made of a game-loop where each frame of your game is a compilation step. Each compilation step is computing a new state of your game, that you can present to your player and also inject to the following frame / compilation step.

I let you contemplate this magnificient diagram for as much time as it takes you to understand what I just wrote above:

Before we move on the implementation details of such a loop, I am sure that you have one question you would like to shoot at me...

"Why would you even do that?"

Do you really think I would let you break my C++ meta-programming idyll with such a fundamental question? Never!

- First and foremost, a compile-time game will have amazing runtime performances since most of the computations are done during the compilation phase. Runtime performance is a key to the success of your AAA game in ASCII art!

- You lessen the probability that a wild crustacean appears in your github repository and ask you to rewrite your game in Rust. His well-prepared speech on security will fall appart as soon as you explain that a dangling pointer cannot exist at compile-time. Smug Haskell programmers might even approve the type-safety of your code.

- You will gain respect from the Javascript hipster kingdom, where any over-complicated framework with a strong NIH syndrom can reign as long as it has a catchy name.

- One of my friend used to say that any line of code from a Perl program provides you de-facto a very strong password. I surely bet that he never tried generating credentials from compile-time C++.

So what? Aren't you satisfied with my answers? Then, maybe your question should have been: "Why could you even do that?".

As a matter of fact, I really wanted to play with the features introduced by C++17. Quite a few of them focus on improving the expressiveness of the language as well as the meta-programming facilities (mainly constexpr). Instead of writing small code samples, I thought that it would be more fun to turn all of this into a game. Pet projects are a nice way to learn concepts that you may not use before quite some time at work. Being able to run the core logic of your game at compile-time proves once a again that templates and constepxr are turing complete subsets of the C++ language.

Meta Crush Saga: an overview

A Match-3 game:

Meta Crush Saga is a tiled-matching game similar to Bejeweled or Candy Crush Saga. The core of the rules consists in matching three or more tiles of the same pattern to increase your scores. Here is sneak peek of a game state I "dumped" (dumping ASCII is pretty damn easy):

R"(

Meta crush saga

------------------------

| |

| R B G B B Y G R |

| |

| |

| Y Y G R B G B R |

| |

| |

| R B Y R G R Y G |

| |

| |

| R Y B Y (R) Y G Y |

| |

| |

| B G Y R Y G G R |

| |

| |

| R Y B G Y B B G |

| |

------------------------

> score: 9009

> moves: 27

)"

The game-play of this specific Match-3 is not so interesting in itself, but what about the architecture running all of this? To understand it, I will try to explain each part of the life cycle of this compile-time game in term of code.

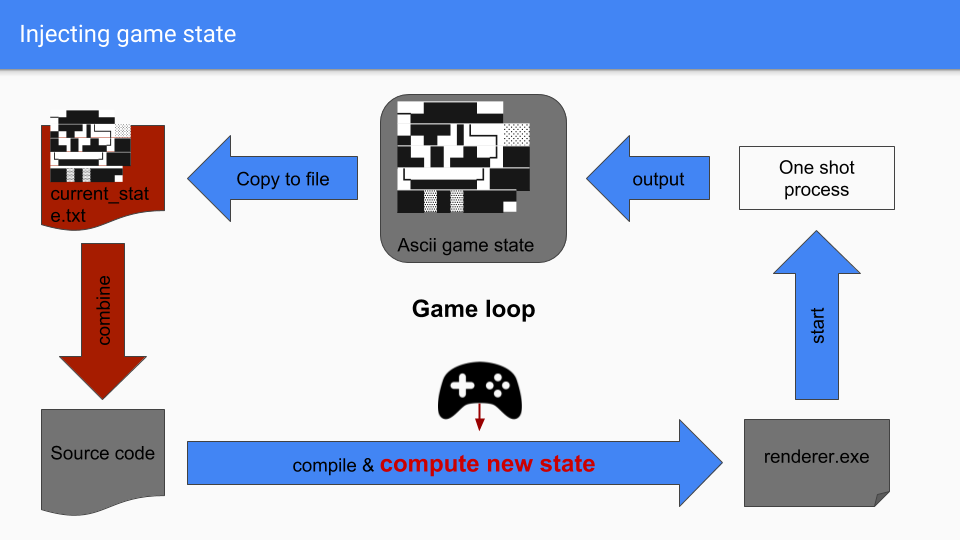

Injecting the game state:

As a C++ afficionados or a nitpicker, you may have noticed that my previous dumped game state started with the following pattern: R"(. This is indeed a C++11 raw string literal, meaning that I do not have to escape special characters like line feed. This raw string literal is stored in a file called current_state.txt.

How do we inject this current game state into a compile state? Let's just include it into the loop inputs!

// loop_inputs.hpp

constexpr KeyboardInput keyboard_input = KeyboardInput::KEYBOARD_INPUT; // Get the current keyboard input as a macro

constexpr auto get_game_state_string = []() constexpr

{

auto game_state_string = constexpr_string(

// Include the raw string literal into a variable

#include "current_state.txt"

);

return game_state_string;

};

Whether it is a .txt file or a .h file, the include directive from C preprocessor will work exactly the same: it will copy the content of the file at its location. Here I am copying the ascii-game-state-raw-string-literal into a variable named game_state_string.

Note that this header file loop_inputs.hpp also exposes the keyboard inputs for the current frame / compilation. Unlike the game state, the keyboard state is fairly small and can be easily received as a preprocessor definition.

Compile time computation of the new state:

Now that we have gathered enough data, we can compute a new state. And finally, we reach the point where we have to write a main.cpp file:

// main.cpp

#include "loop_inputs.hpp" // Get all the data necessary for our computation.

// Start: compile-time computation.

constexpr auto current_state = parse_game_state(get_game_state_string); // Parse the game state into a convenient object.

constexpr auto new_state = game_engine(current_state) // Feed the engine with the parsed state,

.update(keyboard_input); // Update the engine to obtain a new state.

constexpr auto array = print_game_state(new_state); // Convert the new state into a std::array<char> representation.

// End: compile-time computation.

// Runtime: just render the state.

for (const char& c : array) { std::cout << c; }

Strangely, this C++ code does not look too convoluted for what it does. Most of this code is run during the compilation phase and yet follows traditional OOP and procedural paradigms. Only the rendering, the last line, is an impediment to a pure compile-time computation. By sprinkling a bit of constexpr where it should, you can have pretty elegant meta-programming in C++17 as we will see later-on. I find it fascinating the freedom C++ gives us when it comes to mix runtime and compile-time execution.

You will also notice that this code only execute one frame, there is no game-loop in here. Let's solve that issue!

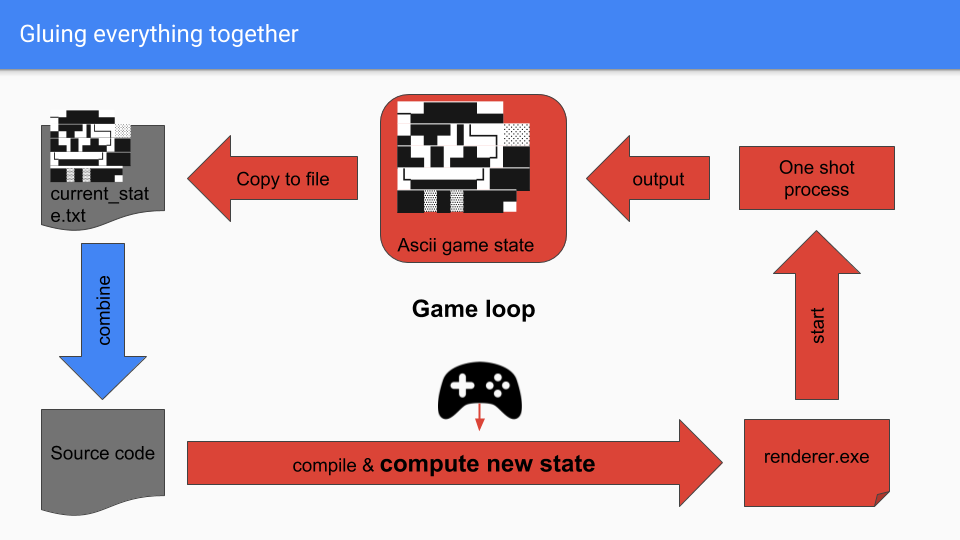

Gluing things together:

If you are revulsed by my C++ tricks, I wish you do not mind to contemplate my Bash skills. Indeed, my game loop is nothing more than a bash script executing repeatidly some compilations.

# It is a loop! No wait, it is a game loop!!!

while; do :

# Start a compilation step using G++

g++ -o renderer main.cpp -DKEYBOARD_INPUT="$keypressed"

keypressed=get_key_pressed()

# Clean the screen.

clear

# Obtain the rendering

current_state=$(./renderer)

echo $current_state # Show the rendering to the player

# Place the rendering into a current_state.txt file and wrap it into a raw string literal.

echo "R\"(" > current_state.txt

echo $current_state >> current_state.txt

echo ")\"" >> current_state.txt

done

I actually struggled a bit to get the keyboard inputs from the console. I initially wanted to receive the inputs in parallel of the compilation. After lots trial and error, I got something working-ish using the read Bash command. I would never dare to duel a Bash wizard, that language is way too maleficent!

Now let's agree, I had to resort to use another language to handle my game loop. Although, technically, nothing would prevent me to write that part of the code in C++. It also does not cancel the fact that 90% of the logic of my game is done within this g++ compilation command, which is pretty awesome!

A bit of gameplay to soften your eyes:

Now that you have suffered your way into my explanations on the game's architecture, here comes a bit of eye candy:

This pixelated gif is a record of me playing Meta Crush Saga. As you can see, the game runs smoothly enough to make it playable in real-time. It is clearly not attractive enough to be able to stream it on Twitch and for me to become the new Pewdiepie, but hey... it works! One of the funny aspect of having a game state stored as a .txt is the ability to cheat or test edge-cases really easily.

Now that I sketched the architecture, we will dive a bit more in the C++17 features used within that project. I will not focus on the game logic, as it is very specific to a Match-3, but will instead discuss subjects of C++ that be could applied in other projects too.

My C++17 learnings:

Unlike C++14 which mainly contained minor fixes, the new C++17 standard has a lot to offer. There were hopes that some long-overdue features would land this time (modules, coroutines, concepts...) and... well... they did not ; which disappointed quite a few of us. But after the mourning, we discovered a myriad of small unexpected gems that made their way through.

I would dare to say that all the meta-programming kids were spoiled this year! Few minor tweaks and additions in language now permit you to write code very similar weither it is running during compilation or afterwards during runtime.

Constepxr all the things:

As Ben Deane and Jason Turner foretold in their C++14 talk, C++ is quickly improving value-computations at compile-time using the almighty constexpr keyword. By placing this keyword in the appropriate places you can hint to your compiler that an expression is constant and could be directly evaluated at compile-time. In C++11 you could already write such code:

constexpr int factorial(int n) // Combining a function with constexpr make it potentially evaluable at compile-time.

{

return n <= 1? 1 : (n * factorial(n - 1));

}

int i = factorial(5); // Call to a constexpr function.

// Can be replace by a good compiler by:

// int i = 120;

While powerful, constexpr had quite a lot of restrictions on its usage and made it cumbersome to write expressive code in this way. C++14 relaxed a lot constexpr and felt much more natural to use. Our previous factorial function could be rewritten this way:

constexpr int factorial(int n)

{

if (n <= 1) {

return 1;

}

return n * factorial(n - 1);

}

Indeed, C++14 lifted the rule stipulating that a constexpr function must only consist of one return statement, which forced us to use the ternary operator as a basic building block. Now C++17 brought even more placements for the constexpr keyword that we can explore!

Compile-time branching:

Did you ever end-up in a situation where you wish that you could have different behavior according to the template parameter you are manipulating? Let's say that you wanted a generic serialize function that would call .serialize() if your object provides one, otherwise fall back on calling to_string on it. As explained in more details in this post about SFINAE you would very likely write such a lovely alien code:

template <class T>

std::enable_if_t<has_serialize_v<T>, std::string>

serialize(const T& obj) {

return obj.serialize();

}

template <class T>

std::enable_if_t<!has_serialize_v<T>, std::string>

serialize(const T& obj) {

return std::to_string(obj);

}

In your dreams you may be able to rewrite that awkward SFINAE trick into such a magestic piece of code in C++14:

// has_serialize is a constexpr function that test the of serialize on a object.

// See my post on SFINAE to understand how to write such a function.

template <class T>

constexpr bool has_serialize(const T& /*t*/);

template <class T>

std::string serialize(const T& obj) { // We know that constexpr can be placed before functions.

if (has_serialize(obj)) {

return obj.serialize();

} else {

return std::to_string(obj);

}

}

Sadly, as soon as you wake-up and start writing C++14 for real, your compiler will vomit you a displeasant message regarding the call serialize(42);. It will explain that the object obj of type int does not have a serialize() member function. As much as you hate it, your compiler is right! Given the current code, it will always try to compile both of the branches return obj.serialize(); and

return std::to_string(obj);. For an int, the branch return obj.serialize(); might well be some dead-code since has_serialize(obj) will always return false, but your compiler will still need to compile-it.

As you may expect, C++17 save us from such an embarassing situation by introducing the possibility to add constexpr after an if statement to "force" a compile-time branching and discard the unused statements:

// has_serialize...

// ...

template <class T>

std::string serialize(const T& obj)

if constexpr (has_serialize(obj)) { // Now we can place constexpr on the 'if' directly.

return obj.serialize(); // This branch will be discarded and therefore not compiled if obj is an int.

} else {

return std::to_string(obj);branch

}

}

This is clearly a huge improvement compared to the SFINAE trick we had to employ until now. After that, you will start to get the same addiction as Ben and Jason which consists in constexpr everything, everywhere at anytime. Alas, there is still one place where the constexpr keyword would well fit in but cannot be done yet: constexpr parameters.

Constexpr parameters:

If you are assiduous, you may have noticed a strange pattern in one my previous code sample. I am talking about the loop inputs:

// loop_inputs.hpp

constexpr auto get_game_state_string = []() constexpr // Why?

{

auto game_state_string = constexpr_string(

// Include the raw string literal into a variable

#include "current_state.txt"

);

return game_state_string;

};

Why is the variable game_state_string encapsulated into a constexpr lambda? Why not making it a constexpr global variable?

Well, I wanted to pass this variable and its content deep down to some functions. For instance, my parse_board needed to be fed with it and used it in some constant expressions:

constexpr int parse_board_size(const char* game_state_string);

constexpr auto parse_board(const char* game_state_string)

{

std::array<GemType, parse_board_size(game_state_string)> board{};

// ^ ‘game_state_string’ is not a constant expression

// ...

}

parse_board(“...something...”);

If you are doing it this way, your grumpy compiler will complain that the parameter game_state_string is not a constant expression. When I am building my array of Gems, I need to compute its fixed capacity directly (you cannot use vectors at compile-time as it requires to allocate) and pass it as a value-template-argument to std::array. The expression parse_board_size(game_state_string) therefore needs to be a constant expression. While parse_board_size is clearly marked as constexpr, game_state_string is not AND cannot be! Two rules are annoying us in this case:

- Arguments of a constexpr function are not constexpr!

- And you cannot add constexpr in front of them!

It boils down to the fact that constexpr functions MUST be usable for both runtime or compile-time computations. Allowing constexpr parameters would discard the possibility to use them at runtime.

Thanksfully, there is a way to mitigate that issue. Instead of accepting the value as a normal function parameter, you can encapsulate that value into a type and pass that type as a template parameter:

template <class GameStringType>

constexpr auto parse_board(GameStringType&&) {

std::array<CellType, parse_board_size(GameStringType::value())> board{};

// ...

}

struct GameString {

static constexpr auto value() { return "...something..."; }

};

parse_board(GameString{});

In this code sample, I am creating a struct type GameString which has a static constexpr member function value() that returns the string literal I want to pass to parse_board. In parse_board I receive this type through the template parameter GameStringType thanks to template argument deduction rules. Having GameStringType, I can simply call the static member function value() whenever I want to get the string literal, even in locations where constant expressions are necessary since value() is constexpr.

We succeeded to encapsulate our literal to somehow pass it to parse_board in a constexpr way. Now, it gets very annoying to have to define a new type everytime you want to send a new literal to parse_board: "...something1...", "...something2...". To solve that issue in C++11, you can rely on some ugly macros and few indirection using an anonymous union and a lambda. Mikael Park has a nice explanation on this topic in one of his post.

We can do even better in C++17. If you list our current requirements to pass our string literal, we need:

- A generated function

- Which is constexpr

- With a unique or anonymous name

This requirements should ring a bell to you. What we need is a constexpr lambda! And C++17 rightfully added the possibility to use the constexpr keyword on a lambda. We could rewrite the code sample in such a way:

template <class LambdaType>

constexpr auto parse_board(LambdaType&& get_game_state_string) {

std::array<CellType, parse_board_size(get_game_state_string())> board{};

// ^ Allowed to call a constexpr lambda in this context.

}

parse_board([]() constexpr -> { return “...something...”; });

// ^ Make our lambda constexpr.

Believe me, this feels already much neater than the previous C++11 hackery using macros. I discovered this awesome trick thanks to Björn Fahller, a member of the C++ meetup group I participate in. You can read more about this trick on his blog. Note also that the constexpr keyword is actually not necessary in this case: all the lambdas with the capacity to be constexpr will be by default. Having an explicit constexpr in the signature just makes it easier to catch mistakes.

Now you should understand why I was forced to use a constexpr lambda to pass down the string representing my game state. Have a look at this lambda and one question should arise again. What is this constexpr_string type I also use to wrap the string literal?

constexpr_string and constexpr_string_view:

When you are dealing with strings, you do not want to deal with them the C way. All these pesky algorithms iterating in a raw manner and checking null ending should be forbidden! The alternative offered by C++ is the almighty std::string and STL algorithms. Sadly, std::string may have to allocate on the heap (even with Small String Optimization) to store their content. One or two standards from now we may benefit from constexpr new/delete or being able to pass constexpr allocators to std::string, but for now we have to find another solution.

My approach was to write a constexpr_string class which has a fixed capacity. This capacity is passed as a value template parameter. Here is a short overview of my class:

template <std::size_t N> // N is the capacity of my string.

class constexpr_string {

private:

std::array<char, N> data_; // Reserve N chars to store anything.

std::size_t size_; // The actual size of the string.

public:

constexpr constexpr_string(const char(&a)[N]): data_{}, size_(N -1) { // copy a into data_ }

// ...

constexpr iterator begin() { return data_; } // Points at the beggining of the storage.

constexpr iterator end() { return data_ + size_; } // Points at the end of the stored string.

// ...

};

My constexpr_string class tries to mimic as closely as possible the interface of std::string (for the operations that I needed): you can query the begin and end iterators, retrive the size, get access to data, erase part of it, get a substring using substr, etc. It makes it very straightforward to transform a piece of code from std::string to constexpr_string. You may wonder what happens when you want to do use operations that would normally requires an allocation in std::string. In such cases, I was forced to transform them into immutable operations that would create new instance of constexpr_string.

Let's have a look at the append operation:

template <std::size_t N> // N is the capacity of my string.

class constexpr_string {

// ...

template <std::size_t M> // M the capacity of the other string.

constexpr auto append(const constexpr_string<M>& other)

{

constexpr_string<N + M> output(*this, size() + other.size());

// ^ Enough capacity for both. ^ Copy the first string into the output.

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < other.size(); ++i) {

output[size() + i] = other[i];

^ Copy the second string into the output.

}

return output;

}

// ...

};

No needs to have a Fields Medal to assume that if we have a string of size N and a string or size M, a string of size N + M should be enough to store the concatenation. You may waste a bit of "compile-time storage" since both of your strings may not use their full capacity, but that is a fairly small price to pay for a lot of convenience. I, obviously, also wrote the counterpart of std::string_view which I named constexpr_string_view.

Having these two classes, I was ready to write elegant code to parse my game state. Think about something like that:

constexpr auto game_state = constexpr_string(“...something...”);

// Let's find the first blue gem occurence within my string:

constexpr auto blue_gem = find_if(game_state.begin(), game_state.end(),

[](char c) constexpr -> { return c == ‘B’; }

);

It was fairly simple to iterate over the gems on my board - speaking of which, did you notice another C++17 gem in that code sample?

Yes! I did not have to explicitely specify the capacity of my constexpr_string when constructing it. In the past, you had to explicitely specify the arguments of a class template when using it. To avoid this pain, we would provide make_xxx functions since parameters of function templates could be deduced. Have a look on how class template argument deduction is changing our life for the better:

template <int N>

struct constexpr_string {

constexpr_string(const char(&a)[N]) {}

// ..

};

// **** Pre C++17 ****

template <int N>

constexpr_string<N> make_constexpr_string(const char(&a)[N]) {

// Provide a function template to deduce N ^ right here

return constexpr_string<N>(a);

// ^ Forward the parameter to the class template.

}

auto test2 = make_constexpr_string("blablabla");

// ^ use our function template to for the deduction.

constexpr_string<7> test("blabla");

// ^ or feed the argument directly and pray that it was the good one.

// **** With C++17 ****

constexpr_string test("blabla");

// ^ Really smmoth to use, the argument is deduced.

In some tricky situations, you may still need to help your compiler to deduce correctly your arguments. If you encouter such an issue, have a look at user-defined deduction guides.

Free food from the STL:

Alright, you can always rewrite things by yourself. But did the committee members kindly cooked something for us in the standard library?

New utility types:

C++17 introduced std::variant and std::optional to the common vocabulary types, with constexpr in mind. While the former one is really interesting since it permits you to express type-safe unions, the implementation provided in the libstdc++ library with GCC 7.2 had issues when used in constant expressions. Therefore, I gave up the idea to introduce std::variant in my code and solely utilised std::optional.

Given a type T, std::optional allows you to create a new type std::optional

template <class Predicate>

constexpr std::optional<std::pair<int, int>> find_in_board(GameBoard&& g, Predicate&& p) {

for (auto item : g.items()) {

if (p(item)) { return {item.x, item.y}; } // Return by value if we find such an item.

}

return std::nullopt; // Return the empty state otherwise.

}

auto item = find_in_board(g, [](const auto& item) { return true; });

if (item) { // Test if the optional is empty or not.

do_something(*item); // Can safely use the optional by 'deferencing' with '*'.

/* ... */

}

Previously, you would have recourse to either pointer semantics or add an "empty state" directly into your position type or return a boolean and take an out parameter. Let's face it, it was pretty clumsy!

Some already existing types also received a constexpr lifting: tuple and pair. I will not explain their usage as a lot have been already written on these two, but I will share you one of my disapointment. The committee added to the standard a syntactic sugar to extract the values hold by a tuple or pair. Called structured binding, this new kind of declaration uses brackets to define in which variables you would like to store the exploded tuple or pair:

std::pair<int, int> foo() {

return {42, 1337};

}

auto [x, y] = foo();

// x = 42 and y = 1337.

Really clever! It is just a pity that the committee members [could not, would not, did not have the time, forgot, enjoyed not] to make it constexpr friendly. I would have expected something along the way:

constexpr auto [x, y] = foo(); // OR

auto [x, y] constexpr = foo();

We now have fancy containers and utilities, how can we manipulate them easily?

Algorithms:

Upgrading a container to a handle constexpr is a rather tedious work. Comparatively, bringing constexpr to non-modifying algorithms seems rather straightforward. But strangely enough, C++17 did not see any progress in that domain, it is actually coming in C++20. For instance, the supreme std::find algorithms did not receive its constexpr signature.

Worry not (or "Qu'à cela ne tienne" in French)! As explained by Ben and Jason, you can easily turn an algorithm in constexpr by simply copying a current implementation (checkout for copyrights though) ; cppreference being a good fit. Ladies and gentlemen, I present you a constexpr std::find:

template<class InputIt, class T>

constexpr InputIt find(InputIt first, InputIt last, const T& value)

// ^ TADAMMMM!!! I added constexpr here.

{

for (; first != last; ++first) {

if (*first == value) {

return first;

}

}

return last;

}

// Thanks to: http://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/algorithm/find

I already hear optimisation affionados screaming on their chair! Yes, just adding constexpr in front of a code sample gently provided by cppreference may not give you the perfect runtime performances. But if we really had to polish this algorithm it would be for compile-time performances. Keeping things simple usually give the best results when it comes to speed of compilation from what I observed.

Performance & bugs:

Every triple A games must put efforts in these topics, right?

Performance:

When I achieved a first half-workingish version of Meta Crush Saga things ran rather smoothly. It actually reached a bit more than 3 FPS (Frame Per Second) on my old laptop with an i5 clocked at 1.80GHz (frequency do matter in this case). As in any project, I quickly found my previously written code unsavoury and started to rewrite the parsing of my game state using constexpr_string and standard algorithms. Although it made my code much more maintenable it also had a severe impact on the performance ; 0.5 FPS was the new ceiling.

Unlike the old C++ adage, "zero-head abstractions" did not apply to compile-time computations. Which really makes sense if you see your compiler as an interpreter of some "compile-time code". There is still room to improve for the various compilers, but also for us writers of such code. Here is a non-exhaustive list of few observations and tips, maybe specific to GCC, that I figured out:

- C arrays performed significantly better than std::array. std::array is a bit of modern C++ cosmetic over a C-style array and one must pay a certain price to use it in such circumstances.

- It felt like recursive functions had the advantage (speed-wise) over writing functions with loops. It could well be that writing recursive algorithms forces you to tackle your problems in another way, which behaves better. To put in my two penny worth, I believe that the cost of compile-time calls might be smaller than executing a complicated function body especially that compilers (and their implementors) have been exposed to decades of abusive recursions we used for our own template-metaprogramming ends.

- Copying data around is also quite expensive, notably if you are dealing with value types. If I wanted to futher optimise my game, I would mainly focus on that problem.

- I only

abused one of my CPU core to do the job. Having only one compilation unit restricted me to spawn only one instance of GCC at a time. I am not quite sure if you could parallelise my compilutation.

Bugs:

More than once, my compiler regurgitated terrible compilation errors, my code logic being flawed. But how could I find where the bug was located? Without debugger and printf, things get complicated. If your metaphoric programming beard is not up to your knees (both my metaphoric and physical one did not reach the expectations), you may not have the motivation to use templight nor to debug your compiler.

More than once, my compiler regurgitated terrible compilation errors, my code logic being flawed. But how could I find where the bug was located? Without debugger and printf, things get complicated. If your metaphoric programming beard is not up to your knees (both my metaphoric and physical one did not reach the expectations), you may not have the motivation to use templight nor to debug your compiler.

Your first friend will be static_assert, which gives you the possibility to test the value of a compile-time boolean. Your second friend will be a macro to turn on and off constexpr wherever possible:

#define CONSTEXPR constexpr // compile-time No debug possible

// OR

#define CONSTEXPR // Debug at runtime

By using this macro, you can force the logic to execute at runtime and therefore attach a debugger to it.

Meta Crush Saga II - Looking for a pure compile-time experience:

Clearly, Meta Crush Saga will not win The Game Awards this year. It has some great potential, but the experience is not fully compile-time YET, which may be a showstopper for hardcore gamers... I cannot get rid-of the bash script, unless someone add keyboard inputs and impure logic during the compilation-phase (pure madness!). But I believe, that one day, I could entirely bypass the renderer executable and print my game state at compile-time:

A crazy fellow pseudo-named saarraz, extended GCC to add a static_print statement to the language. This statement would take a few constant expressions or string literals and output them during the compilation. I would be glad if such tool would be added to the standard, or at least extend static_assert to accept constant expressions.

Meanwhile, there might be a C++17 way to obtain that result. Compilers already ouput two things, errors and warnings! If we could somehow control or bend a warning to our needs, we may already have a decent output. I tried few solutions, notably the deprecated attribute:

template <char... words>

struct useless {

[[deprecated]] void call() {} // Will trigger a warning.

};

template <char... words> void output_as_warning() { useless<words...>().call(); }

output_as_warning<’a’, ‘b’, ‘c’>();

// warning: 'void useless<words>::call() [with char ...words = {'a', 'b', 'c'}]' is deprecated

// [-Wdeprecated-declarations]

While the output is clearly there and parsable, it is unfortunately not playable! If by sheer luck, you are part of the secret-community-of-c++-programmers-that-can-output-things-during-compilation, I would be glad to recruit you in my team to create the perfect Meta Crush Saga II!

Conclusion:

I am done selling you my scam game. Hopefully you found this post ludic and learned things along the reading. If you find any mistake or think of any potential improvement, please to do not hesitate to reach me.

I would like to thanks the SwedenCpp team for letting me having my talk on this project during one of their event. And I particularly would like to express my gratitude to Alexandre Gourdeev who helped me improve Meta Crush Saga in quite a few significant aspects.