Making a STL-compatible hash map from scratch - Part 1 - Beating std::unordered_map

Posted on Mon 06 April 2020 in C++

This post is part of a planned series of posts:

- Part 1 - Beating std::unordered_map (Current)

- Part 2 - Growth Policies & The Schrodinger std::pair

- Part 3 - The wonderful world of iterators and allocators

- Part 4 - An insertion maze (Coming Soon)

Part 1 - Beating std::unordered_map

Trivia:

If C++ had an equivalent in the video game world, it would be similar to Dark Souls: a dark, violent, punishing game. Yet, the emotion you get after successfully assimilating all the moves required to overcome a challenge is absolutely impossible to replicate. You are able to reproduce a sort of dance to defeat any boss in your way. Speaking of which... what could be the final boss of C++? According to Stephan T. Lavavej (STL) this would be the Floating-Point charconv of the C++17's standard. While I wouldn't be able to beat this boss by myself anytime soon, I can tackle a tiny boss: making a standard-compatible (but not necessarily standard-compliant) container from scratch. I would like to share with you how to beat this kind of smaller bosses by yourself!

We will build a unordered_map together, with all the arcane beasts that come along: iterators, allocators, type traits... and we will survive it.

I encourage you to read this post as an introduction to the wonderful world of hash maps and the ways of the standard. You can find the code for the hash-map I am describing thorough this series of posts right here. Hopefully when you are done reading this series, you will be ready to explore a bit more what the talented people in the C++ community have produced recently.

Disclaimer: there are lots of extremely talented people (abseil team with their Swiss Tables, Malte Skarupke's flat hash map...) that have been researching for years how to make the quintessence of an associative container. While the one I am presenting here has a really decent performance (more so than the standard ones at least), it is not bleeding-edge. On the other hand, its design is fairly simple to explain and easy to maintain.

Freeing ourselves from the standard constraints:

Implementing a standard associative container like std::unordered_map wouldn't be satisfying enough.

We have to do better! Let's make a faster one!

The standard library (and its ancestor the STL) is almost as old as me.

You would think that the people working on an implementation of it (libc++, libstdc++...) would have had enough to polish it until there is no room to improvement.

So how could we beat them in their own domain? Well... we are going to cheat... but in a good way.

The standard library is made to be used by the commoners.

The noble ladies and gentlemen in the standard committee stated some constraints to protect us from killing ourselves while using their std::unordered_map.

May this over-protective behaviour be damned! We know better!

Breaking stable addressing

The standard implicitly mandates stable addressing for any implementation of std::unordered_map.

Stable addressing means that the insertion or deletion of a key/value pair in a std::unordered_map should not affect the memory location of other key/value pairs in the same std::unordered_map. More precisely, the standard does not mention, in the Effects sections of std::unordered_map's modifiers, anything about reference, pointer or iterator invalidation.

This forces any standard implementation of std::unordered_map to use linked-list for the buckets of pairs rather than contiguous memory.

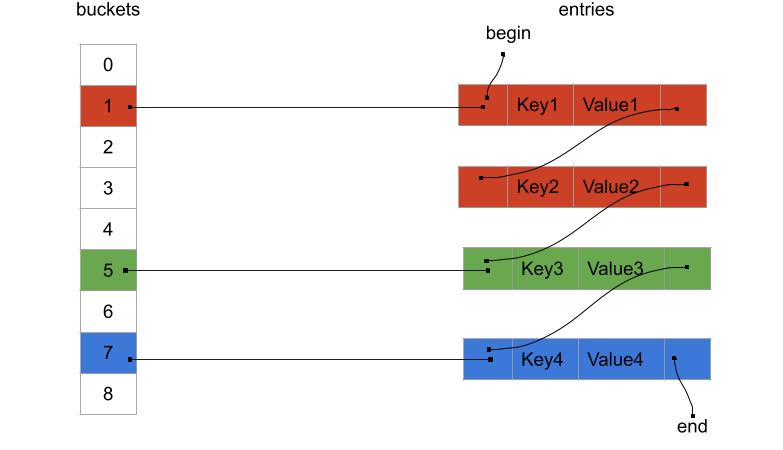

std::unordered_map should look roughly like this in memory:

As you can see, the entries are stored in a giant linked-list. Each of the buckets are themselves sub-parts of the linked-list.

Here each colors represent different buckets of key/value pairs.

When a key/value pair is inserted, the key is somehow hashed and adjusted (usually using modulo on the amount of buckets) to find which bucket it belongs to, and the key/value pair gets inserted into that bucket.

Here, the key1 and key2 somehow ended-up belonging to the bucket 1.

Whereas the key3 belongs to the bucket 5.

When doing a lookup using a key, the key is hashed and adjusted to find the bucket it should belong to.

The bucket of the key is iterated until the key is found or the end of the bucket is reached (meaning no key is in the map).

Finally, the buckets are linked between each others to be able to do a traversal of all the key/value pairs within the std::unordered_map.

This memory layout is really bad for your CPU! Each of the nodes of the linked-list(s) could be spread across memory and that would play against all the caches of your CPU. Traversing buckets made of a linked-list is slow, but you could pray that your hash function save you by spreading keys as much as possible and therefore have tiny buckets. But even the most brilliant hash function will not help you with a common use-case of an associative container: iterating through all the key/value pairs. Each dereference of the pointer to the next node will be a huge drag on your CPU. On the other hand, since each node are separately allocated, they can stay wherever they are in memory even if others are added or removed, which provides stable addressing.

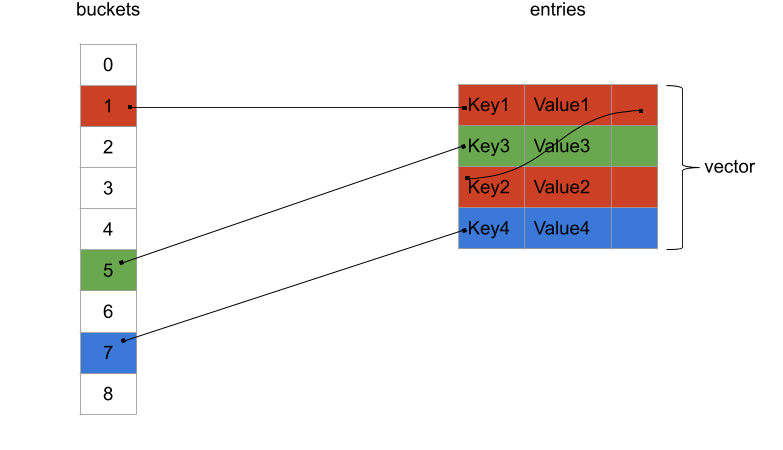

So what could we obtain if we were to free ourselves from stable addressing? Well, we could wrap our buckets into contiguous memory like so:

Here we are still keeping a linked-list for each buckets, but all the nodes are stored in a vector, therefore one after each others in memory. Let's call this a dense hash map. Instead of using pointers between nodes, we are expressing their relations with indexes within the vector: here the node with key1 store a "next index" having a value of 2 which is the index of the node with key2. And all of that is a huge improvement! We are gaining on all fronts:

- Iterating over all the key/value pairs is as fast as iterating over a vector, which is lightning fast.

- We are saving a pointer on all nodes - the "prev pointer". We don't need any sort of reverse-traversal of a given bucket, but just a global reverse-traversal of all buckets.

- We don't need to maintain a begin and end pointer for the list of nodes.

- Even iterating over a bucket could be faster as the node shouldn't be too scattered in memory since they all belong to one vector.

All these new properties have a lot of use-cases in the domains I dabble with. For instance, the ECS (Entity-Component-System) pattern often demands a container where you can do lookup for a component associated to a given entity and at the same being able to traverse all components in one-shot.

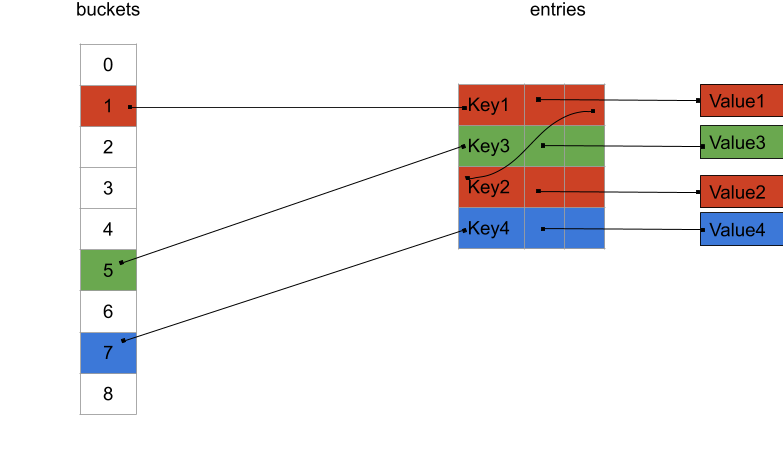

With that said, the stable addressing is now gone: any insertion into the vector could produce a reallocation of its internal buffer, ending in a massive move of all the nodes across memory. So what if your user really need stable addressing? As David Wheeler would say: "just use another level of indirection".

Instead of a using a dense_hash_map<Key, Value>, your user can always use a dense_hash_map<Key, unique_ptr<Value>>:

We are reintroducing pointers, which is obviously not great for the cache again. But this time when iterating over all the key/value pairs you will very likely see a substantial improvement over the first layout. The pattern of the nodes is clearly more predictable and prefetching abilities of your CPU may come to your help.

There a lot more layouts for hash tables that I did not mention here and could have suited my needs. For instance, any of the open-addressing strategies could bring their own pros and cons. Once again, if you are interested, there are a plethora of cppcon talks on that subject.

Caveats

By breaking stable-addressing, we cannot retain the address or the reference of a key-value pair from our map carelessly. Some operations like adding or removing a key/value pair in the map can provoke invalidation of references or pointers to the other pairs. This is the kind of danger I am speaking of:

jg::dense_hash_map<std::string, hero> my_map{{"spongebob", hero{}}, {"chuck norris", hero{}}};

auto& chuck_ref = my_map["chuck norris"];

my_map.erase("spongebob"); // Invalidate all the nodes after spongebob.

chuck_ref.punch_your_face(); // One should never try to retain "chuck norris" as a ref.

Due to the call to erase, "chuck norris" is moved into the first slot of the internal vector, which ultimately makes chuck's address change. Accessing "chuck norris" with a previously acquired reference becomes a danger. While this can surprise at first, it is no different than trying to retain a reference to a value in a vector. And once again, if you need stable addressing, you are welcome to store unique_ptrs within your map.

For the same stable-addressing reasons, implementing the node API of std::unordered_map like extract becomes very challenging. To be fair, I have never seen a real usage of that API in any project. It might be useful in scenarios where you run long instances of backend-applications and want to move things across maps without a huge performance impact. If by any chance, you have witnessed a usage of that feature, it would be a pleasure to have some explanations in the comments section.

Finally, as we will see in a later post, the erase operation of such dense_hash_map becomes slower. For any erase operation, one extra swap operation is needed on top of the destruction and deallocation ones. Thankfully, a standard usage of a map will have little erase operations compared to lookup or even insertion operations. Speaking of which, how could we improve on those operations?

Faster modulo operation

As I mentioned previously, a lookup will require that your key is hashed and adjusted with modulo to fit in the amount of buckets available.

The amount of buckets is changing depending on how many key/value pairs are stored in your map. The more pairs, the more buckets.

In a std::unordered_map, the growth is triggered every time the load factor (average number of elements per bucket) is above a certain threshold.

Adjusting your hash with a "simple modulo operation" is as it turns out not a trivial operation for your hardware.

Let's godbolt a bit!

If we write a simple modulo function, this is what godbolt gives to us (on GCC 9.0 with -O3):

// C++

int modulo(int hash, int bucket_count)

{

return hash % bucket_count;

}

// x86 assembly

modulo(int, int):

mov eax, edi // Prepare the hash into eax

cdq // Prepare registers for an idiv operation.

idiv esi // Divide by esi which contains bucket_count

mov eax, edx // Get the modulo value that ends-up in edx and return it into eax

ret

So far things look rather good. The idiv operation seems to do most of the work by itself.

But, what if we made bucket_count a constant? Having more information at compile-time should help the compiler, isn't it?

// C++

int modulo(int hash)

{

return index % 5;

}

// x86

modulo(int, int):

movsx rax, edi

mov edx, edi

imul rax, rax, 1717986919 // LOTS OF SHENANIGANS GOING HERE.

sar edx, 31

sar rax, 33

sub eax, edx

lea eax, [rax+rax*4]

sub edi, eax

mov eax, edi

ret

Interesting! The compiler is spitting a lot more operations. Wouldn't it be simpler to keep idiv here? A single operation...

Believe it or not, your compiler is as smart as a whip and wouldn't do this extra work without significant gains.

So we can clearly extrapolate that our innocent idiv must be seriously costly if it happens to be less efficient than a couple of other operations.

So how can we optimize this modulo operation without using idiv or a constant?

We can use bitwise operations and restrict ourselves to sizes made of power of two.

Assuming that y is a power of two in the expression x % y, we can replace this expression with: x & (y - 1).

You can think of this bitwise operation as a "filter" on the lower bits of a number, which happen to be the same as a modulo operation when it comes to power of two.

So what do we obtain in this conditions?

// C++

int fast_module(int hash, int bucket_count) {

return (hash & (bucket_count - 1));

}

// x86

fast_module(int, int):

lea eax, [rsi-1]

and eax, edi

ret

Not only we have less operations, but lea (compute a memory address) and and have much less associated cost than idiv.

This micro-optimisation may look a bit far-fetched, but it actually matters a lot, as proved by Malte Skarupke, when it comes to lookup operations.

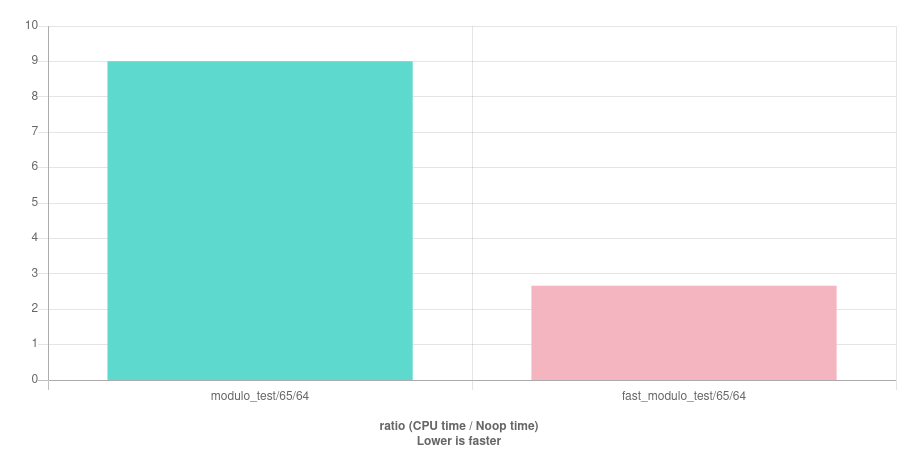

To further convince you, I have run both implementations of modulo on quick-bench. And here are the results:

There is no doubts, using bit operations instead of modulo is indeed faster!

Note: For the purists, the so-called modulo operator % in C++ is actually an integer remainder operator since it does not handle negative value as a mathematical modulo operation would. One can only imagine how costly a proper modulo would be...

Caveats

Unlike the previous improvement, this one does not seem to collide too much with the holly standard. So how come it is not used in every implementations? Well, fiddling with bit operations comes with few drawbacks.

Firstly, the growth of the container for the buckets must always be done following a power of two. This limits you on how creative you can be with your growth strategy. In theory, this could also create subtle performance issues in some scenarios, like cache line collisions. In practice, you should never have an access pattern that triggers such an issue on the container of buckets. It is not like you are going to iterate over that container at any time.

Secondly, in a subtle way you are making the first bits of your keys have more importance than they should. Let's assume that you have some bit flags (flag sets) as a key:

const std::uint32_t a_precious_flag = 1 << 0;

const std::uint32_t another_flag = 1 << 1;

// ...

const std::uint32_t yet_another_flag = 1 << 4;

auto a_set_of_flags = yet_another_flag | a_precious_flag | another_flag;

auto another_set_of_flags = a_precious_flag | another_flag;

jg::dense_hash_map<int, int> my_map; // A map with a buckets container of size 4 (2 ^ 2).

Now, if you were to take these two flag sets and feed them directly to the modulo operation of the map, they would end-up in the same bucket simply because both of them have a_precious_flag and another_flag on. This gives way too much importance to the bits that a_precious_flag and another_flag represent.

The fact that we are using a power two (4 in this case) will always make the lower bits very significant.

It is not often that you store flag sets or bit fields as keys in a map, I will give you that, but as a good practice you should:

- Remind yourself not to create a corner-case with bits more important than others in your key.

- And if it happens, you should re-write your hash function to shuffle your bits around.

First conclusion

Now we have a grand master plan to beat std::unordered_map by removing some assumptions the standard had to make to be preserve us from some dangers.

The hacks used are not even too difficult to grasp, so where is the difficulty in writing new containers? Well, some creepy C++ features are waiting for us around the corner.

Be ready for the next phase: Part 2 - Growth Policies & The Schrodinger std::pair!